Max Ingrand and the elemental power of light and color

|

|

THE COVETED AND ICONIC MASTERPIECE DAHLIA CHANDELIER with 16 curved green glass petals. Max Ingrand for Fontana Arte, Italy, circa 1955. One of a matching pair offered by Donzella. This important example will be on loan to Fontana Arte — House of Glass, a major retrospective exhibition on the history of Fontana Arte to be held at Le Stanze Del Vetro, in Venice, April 4 through July 30, 2022. |

Original Post by Benjamin Genocchio

|

Max Ingrand (1908–1969), the legendary French 20th century designer and interior decorator, is best known for his designs as artistic director for Fontana Arte, the Milan-based lighting and design firm founded by the designer Gio Ponti.

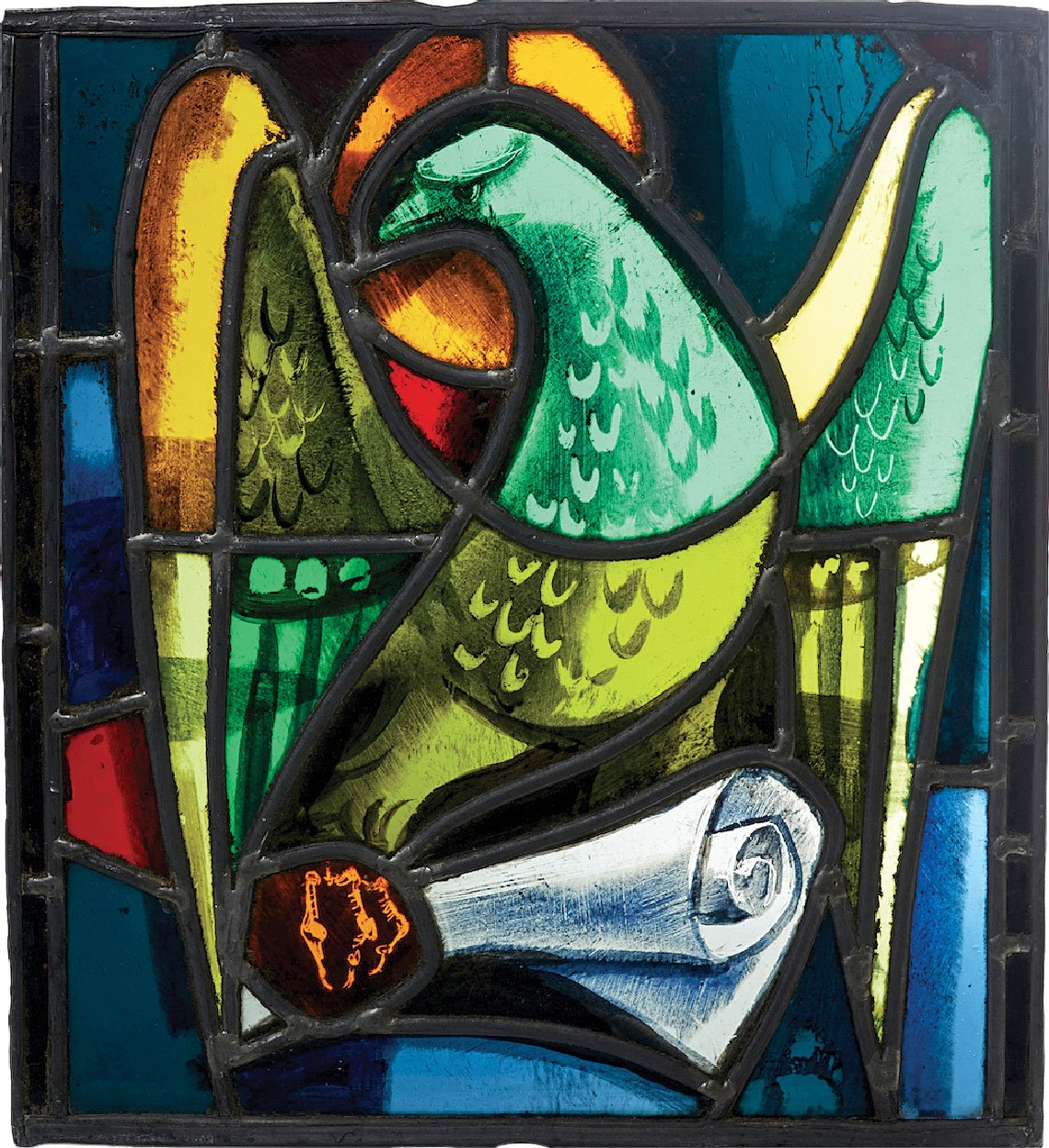

It is less known that for most of his career he worked in the rarified field of making stained glass windows. Ingrand designed windows for hotels, theaters, corporate offices and private residences, and once, for an ocean liner, the ultra-luxurious SS Normandie, which he completed in 1932. However far and away the bulk of his creativity was devoted to majestic stained glass windows for churches — more than 200 religious commissions in all — not just in Europe but for cathedrals and houses of worship in the United States, Canada and beyond, including the nave in Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris.

|

|

|

|

Left: Designed in 1954, the elemental purity and exquisitely graceful proportions of Ingrand’s “Fontana” table lamp rendered it an instant design classic. This 30” version is the largest of the three created. Offered by L’Antiquaire. Right: Illuminated Mirror, by Max Ingrand for Fontana Arte, circa 1960. Circular mirrored pane, trimmed in brass and encompassed by a translucent gray glass disc, affixed with 24 faceted cabochons of mirrored glass. Offered by Bernd Goeckler Antiques. |

||

Ingrand’s justly famous modern designs, produced during his tenure at Fontana Arte from 1954–1968, include several now-classic designs in glass including lamps, sconces, glassware, chandeliers, vases, ashtrays, candlesticks, and tables. Take, for example, the white “Fontana” table lamp, designed by Ingrand in 1954 for Fontana Arte with a lower hand-blown white glass globe and satinated shade, each of which can be illuminated separately. This simple, minimalist lamp was an instant design classic that is still popular today partly because of its timeless simplicity and elegance, but also because the triple light control offers versatility with light levels.

|

|

|

One of a number of pieces from his extensive inventory of works by Max Ingrand NYC dealer Paul Donzella will be on loan to “Fontana Arte — House of Glass,” an important retrospective exhibition to be held this spring in Venice. Rare “Disco Volante” Table Lamp by Max Ingrand for Fontana Arte, circa 1956. Polished and acid-etched glass diffusers in pale rose and natural glass colors and brass base, standard, mounts and finial. Provenance, private collection Sicily. Offered by Donzella. |

Then there are his round concave mirrors, on tempered color glass backing, sometimes with gems surrounding the circular, central mirror plate. Katja Hirche, President of Bernd Goeckler Inc. in New York has been dealing in Ingrand’s work for almost three decades. She has one of Ingrand’s gem circular mirrors in the gallery with faceted crystal chunks attached to brass arms against a curved plate of smoked glass.

“I personally think he is one of the most important glass artists and makers or designers of the 20th century,” says Hirche. As a gallerist I am just as excited about that model [of mirror] now as I was when we had our very first one for sale over 20 years ago.” Hirsche points to Ingrand’s “commitment to impeccable quality” as a key to the success and longevity of his creations, as well as an unparalleled “application of new techniques and upgrading established design and material processes."

Born in Bressuire, France, Ingrand studied decorative arts in Paris, where he trained with a master glassmaker, and in 1931 started his own glass-making workshop. He collaborated with Jules Leleu and André Arbus, earning a reputation for quality and formal innovation in glassmaking. After World War II he was employed repairing damaged stained glass windows until, in 1954, he joined Italian lighting and design company Fontana Arte at the suggestion of his friend Ivan Peychès, Research Director of the French glassmaking company Saint-Gobain.

Paul Donzella, one of New York’s preeminent design dealers and an expert in Italian design also regards Ingrand as one of the most important designers of the 20th century and points to the strength of the artist’s work on the secondary market. For Fontana Arte, Donzella believes, Ingrand was brought in as the design director at an “opportune time” in the company’s trajectory. “I believe his experience working with stained glass was what pushed him to introduce much more color into the work than Fontana Arte previously used. His design aesthetic created a perfect marriage for the company, and he pushed them in directions that hadn’t yet been seen at the time.”

|

|

Dahlia chandelier model 1563 in a rare multi-color version, with 16 curved and tapered petals in alternating tints of blue, rose, yellow and clear glass. Max Ingrand for Fontana Arte, circa 1950s, Italy. Offered by Gaspare Asaro - Italian Modern. |

In addition to being a dealer, Donzella is also a collector of the work of Ingrand and will be lending several works by Ingrand and other designers from his personal collection to Fontana Arte — House of Glass, an important retrospective exhibition on the history of Fontana Arte. Curated by Christian Larsen and designed by architect Massimiliano Locatelli it will be held at Le Stanze Del Vetro, in Venice, April 4 through July 30 this year to coincide with the Venice Biennale. Donzella hopes the show will draw greater attention to Ingrand and the achievements of the designers associated with the history of Fontana Arte.

“The fascinating thing about Fontana Arte’s enormous output,” Donzella says, “was the fact that the company was built on the concept of sheet glass and the many, many ways it could be worked and manipulated into [modern] design and decorative art objects. When you consider that probably 90% of the glass elements of their pieces started out as flat sheets of glass, the work that was produced becomes so much more impressive.”

Ingrand’s designs for Fontana Arte and later, more briefly, for his own lighting company Verre Lumiére which he co-founded in 1968, tend to be simple in form, elegant and refined. But at the same time, they are whimsical and playful, with flourishes of decoration that draw inspiration from the Art Deco style that was so dominant in Europe in the first half of the 20th century and at odds, somewhat, with the orthodoxy of modern design. No one could mistake Ingrand for a student of the Bauhaus.

Ingrand expanded his Dahlia series to include 2 styles of sconces, a two-light version and an exceedingly rare three-light version, and a floor lamp.

|

|

A pair of Dahlia two-light sconces in Ingrand’s classic combination of pale aquamarine and clear crystal. Model 1461, Max Ingrand for Fontana Arte, Italy, circa 1955. Offered by Bloomberry. |

|

|

Dahlia Floor Lamp, circa 1958 in a rare cobalt blue version. Offered by Portuondo. |

“Light, color and architecture,” was his mantra. How can you escape the primordial enchantment of these essentials?” says Gaspare Asaro, owner of the renowned New York design firm Gaspare Asaro and an expert in Italian design. Asaro points to the “Dahlia” series of lighting fixtures as a signature body of design, with brass arms ending in candelabra sockets beneath curved, tempered glass petals radiating out from a cast brass base. Layering creates depth, shadowing that compliments design.

Asaro believes it was Ingrand’s long experience in “filtering natural light through glass” for stained glass windows that was “essential in his development of light fixtures and other objects that filter artificial lights in enclosed spaces.” He also offered the observation that Ingrand’s body of work tends to have in common the same three basic components as used in stained glass: glass, metal, and color; manifested frequently as smoked, tempered, or colored glass, often mixed with clear sheet glass or mirror, with the metal elements used for wiring, structure or support.

|

|

|

|

Suite of 17 stained glass panels representing symbolic images of the Old and New Testament, by Max Ingrand. Two panels are signed “Max Ingrand France.” These rare pieces of early work by Max Ingrand are amongst a few that were commissioned by the Catholique Church of Québec in the 1950s, they remained un-installed until they were purchased by the church of Mont Laurier in Québec, Canada in 1965 after it was rebuilt following a fire. Provenance: Church Coeur-Immaculé-de-Marie, Mont-Laurier, Québec. Offered by Milord Antiques. |

||

|

|

|

|

| Left: Created during the 1950s, a shaped crystal mirror attached with brass mounts, floating on a one-inch thick slab of shaped and curved pale green glass. Presented by L’Art De Vivre, NYC. Right: A rare five-light chandelier of sandwiched pairs of teardrop blades in pale green glass, with sandblasted ovals that diffuse the lighting elements. Max Ingrand for Fontana Arte, model #2338, circa 1960. Offered by Versus Gallery, Munich. | ||

|

|

Ingrand also designed furniture and accessories. His coffee and occasional tables are of particular note. Here, the rare Model #1774 coffee table in black enameled steel with brass detail on the legs, pale green ground glass top over curved mirrored optical glass, circa 1958. Available from Società Antiquaria, Torino, Italy. |

|

“Ingrand reconceived of glass and metal as sensuous and complimentary materials, together capable of forms that — Charles Fuller Gallerist, L’Art De Vivre, NYC |

Florian Specht, from Versus Gallery in Munich, an experienced and knowledgeable dealer of Ingrand’s work, is a particular fan of a rare chandelier, model #2338, that was made for Fontana Arte circa 1962 and consists of parallel hanging, sandblasted heavy teardrop-shaped pieces of glass obscuring brass light sockets. “Here I find the great heavy glass drops absolutely fascinating,” he says. “I also love the coffee tables in brass, in enameled metal and mirrored concave glass, especially the model #1774, produced by Fontana Arte circa 1959.”

Societa Antiquaria has two of Ingrand’s much-coveted model #1774 circular coffee tables designed for Fontana Arte for sale at its Turin gallery, and also available online at Incollect.com. One of the tables has a black metal base and the other has a wood base, though the appeal of the design is chiefly derived from layering a piece of thick, heavy, curved, mirrored optical glass underneath and a piece of ground glass on the top so as to elicit optical illusions out of a flat and functional surface.

Ingrand’s choice and combination of materials, though often commented upon, is one of the most important innovations in his approach to design, according to Charles Fuller from L’Art De Vivre in New York. “Ingrand reconceived glass and metal as sensuous and complimentary materials, together capable of forms that had not been considered possible, or likely, previously,” Fuller says, “This required both aesthetic reconsideration on his part and technical innovations within the context of traditional artisanal work by skilled craftsmen. Today we have advanced technologies that stretch the possibilities with many materials — woods, metal, stone — but Ingrand was able to coax out of glass and metal a new splendor using casting and glass-forming techniques often hundreds of years old, but in entirely new ways.”

|

|

A statement of sensuality in texture and form, this unusual chandelier by Max Ingrand in polished bronze and frosted bias cut glass shades, circa 1960. Presented by L’Art De Vivre, NYC. |

|

|

Pair of sconces by Max Ingrand for Fontana Arte. A rare form in chiseled, etched and satin glass with brass trim and fittings, circa 1960. Offered by Donzella. |

Today Fuller continues to marvel, he says, at the way Ingrand “refused to be limited to the qualities of the material previously attributed to it.” He singles out one of the signature techniques he developed at Fontana Arte, where he “introduced a visually striking technique of chiseling glass, as if it was wood worked in a sculptor’s studio.” Fuller remarks once again on the ways in which he used light to enhance the rich tones of the color-saturated transparent glass in lighting “in an entirely modern way,” creating, in his view, “fluid abstract sculptures”.

“Art” and “sculpture” are words that recur in the appraisals of Ingrand’s work. Fuller sees this most specifically in the small intimate table lamps he produced, “splendid sculptures the equal, in many ways, of Brancusi’s or Barbara Hepworth’s, in miniature,” he says. Hugo Portuondo, from Portuondo Gallery in London agrees. “His visionary designs, the quality of the glasswork, use of materials, the purity and simplicity of the lines and sculptural quality of his designs elevate his work above everyday household furnishings. In our opinion his pieces are more than objects, they are art.”